Mojo 101

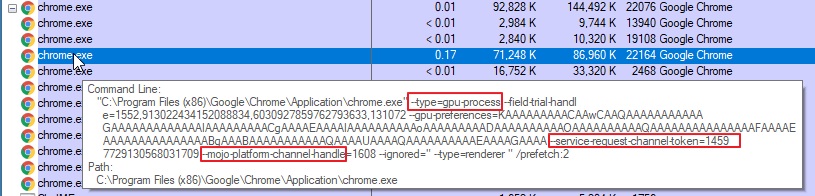

Chrome is built on a multi-process architecture. When you start Chrome, without opening any web page, a dozen more processes are already fired up behind the scene:

The commandline argument type shows that these processes fall into four categories:

| Type | Count | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Main | 1 | Chrome executable run by user |

| Renderer | multiple | 1 per web page |

| Gpu | 1 | Execute Gpu commands for all renderer processes |

| Utility | mutliple | Breakpad handler, watcher etc. |

Launching and managing processes is done by Chrome’s inter-process communication (IPC) system, which consists of two components: Mojo and Service (see those two arguments common to many processes: service-request-channel-token and mojo-platform-channel-handle). In this section, we first take a look on Mojo.

Mojo interface

Mojo provides language bindings so that the interface can be defined in a language-neutral way. It also takes care of routing Mojo interface calls (intra or inter process) from clients to the actual implementation.

Working with Mojo means two things:

- Define and implement interfaces to provide some functionality

- Setup the environment to use the interface as an intra-process or inter-process client

These are two sides of the same coin. Let’s start with defining our first Mojo interface FortuneCookie, it has only one method Crack(), which returns a string:

interface FortuneCookie {

Crack() => (string message);

};

Mojo interfaces are defined in mojom files, which are built with a target type mojom. The BUILD.gn file looks like this:

import("//mojo/public/tools/bindings/mojom.gni")

mojom("mojom") {

sources = [

"fortune_cookie.mojom"

]

}

Note that in the line mojom("mojom"), the first mojom is the target type defined in //mojo/public/tools/bindings/mojom.gni, the second mojom is the name for this target. Because this file is under a directory named mojom, using the same name makes it easier to refer to from higher level build files.

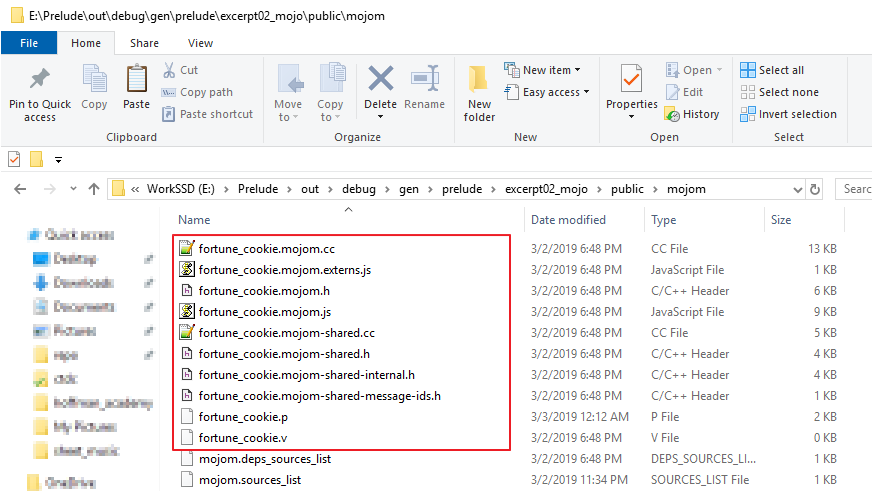

Once compiled, it generates header files in various languages including C++, Java, and Javascript.

With the header files in place, we can work on the implementation:

class FortuneCookieImplAlpha : public mojom::FortuneCookie {

public:

FortuneCookieImplAlpha();

~FortuneCookieImplAlpha() override;

void BindRequest(mojom::FortuneCookieRequest request);

void EatMe();

private:

// mojom::FortuneCookie impl

void Crack(CrackCallback callback) override;

mojo::Binding<mojom::FortuneCookie> binding_;

DISALLOW_COPY_AND_ASSIGN(FortuneCookieImplAlpha);

};

FortuneCookieImplAlpha is different from a regular sub-class in two ways:

- It has a binding object (i.e.,

mojo::Binding<mojom::FortuneCookie>) - The Mojo interface method Crack() is implemented as a private member.

Binding objects hook up Mojo with the implementation so that Mojo knows where to route Mojo interface calls. There are different types of binding objects and mojo::Binding<> is the simplest one. Here in this example, binding_ is set up in two steps: first initialized with this pointer in the constructor; later connect to a Mojo interface request in BindRequest():

FortuneCookieImplAlpha::FortuneCookieImplAlpha() : binding_(this) {}

void FortuneCookieImplAlpha::BindRequest(mojom::FortuneCookieRequest request) {

std::cout << "Fortune cookie binding.\n";

binding_.Bind(std::move(request));

}

Although not required, it’s very common that Mojo interface methods are implemented as private members. This prevents direct calls to these methods which are quite different from calling through Mojo. A public member function EatMe() is defined to show such differences. It prints "Bon appetit.".

Also, notice the difference between the Crack() defined in the mojom file and its generated C++ counterpart, the returning string is wrapped into a callback. This is Mojo’s way of sending data back to the client. In this sample, Crack() prints "crack now." before invoking the callback.

Now let’s look at the client side.

int main(int argc, char** argv) {

CHECK(base::CommandLine::Init(argc, argv));

base::AtExitManager exit_manager_;

// mojo requires a sequenced context, i.e., a message loop in the thread.

base::MessageLoop main_loop;

mojo::core::Init();

auto real_cookie = std::make_unique<prelude::FortuneCookieImplAlpha>();

prelude::mojom::FortuneCookiePtr cookie_ptr;

real_cookie->BindRequest(mojo::MakeRequest(&cookie_ptr));

// although the method is defined as private, it can still be called through

// mojo interface pointer. But this call is asynchronous, which won't run

// until RunLoop().Run() is called

cookie_ptr->Crack(base::DoNothing());

// this call is executed BEFORE Crack() above

real_cookie->EatMe();

base::RunLoop().RunUntilIdle();

return 0;

}

This shows the minimum setup required to use Mojo interface, including:

- A sequenced context, i.e., running thread need to have

base::MessageLoopset up - Call

mojo::core::Init()

Next, create a FortuneCookieImplAlpha instance and bind it to the Mojo interface request. Mojo C++ Bindings API provides in-depth explanations on those strange looking function calls such as mojo::MakeRequest().

Now we are ready to use the Mojo interface pointer (or strongly-typed message pipe endpoint) cookie_ptr. Notice that the code first makes a call to Crack() through Mojo, then directly calls EatMe() (since it’s a public member function) through the smart pointer real_cookie.

The output is shown below:

Fortune cookie binding.

Bon appetit.

crack now.

It’s clear that EatMe() is executed BEFORE Crack() despite the calling order. The reason is that Mojo interface call is asynchronous, it is not run until base::RunLoop().RunUntilIdle() is executed. If you comment out that line, Crack() will never run. Such difference determines that the way to use Mojo interface pointer is quite different from a regular C++ pointer.

Working with Mojo Interface pointer

In last example, a callback that does nothing (i.e., base::DoNothing()) is passed to Crack(). In real life applications, the client usually wants to do something with the returned data. In next example, a callback bound to CopyMessage is passed to Crack(), which copies the returned string into copy_msg.

base::RunLoop loop;

cb = loop.QuitClosure();

cookie_ptr->Crack(base::BindOnce(&CopyMessage, ©_msg));

// since Crack() is called asynchronously, |copy_msg| is empty here

std::cout << "check the copied message synchronously: "

<< (copy_msg.empty() ? "Empty" : copy_msg) << std::endl;

real_cookie->EatMe();

loop.Run();

The copied string is checked in two places: first in main right after Crack() call, then in function PrintAndQuit(). CopyMessage() posts PrintAndQuit() to the current task runner so it is invoked asynchronously.

Imagine task runner as the conveying belt of an assembly line. And functions (i.e., tasks) are the parts put (i.e., posted) on the belt, which will be worked on later.

std::string copy_msg;

base::Closure cb;

void PrintAndQuit() {

std::cout << "check the copied message asynchronously: " << copy_msg

<< std::endl;

std::move(cb).Run();

}

void CopyMessage(std::string* out_msg, const std::string& in_msg) {

std::cout << "Copy message: " << in_msg << std::endl;

*out_msg = in_msg;

base::SequencedTaskRunnerHandle::Get()->PostTask(

FROM_HERE, base::BindOnce(&PrintAndQuit));

}

The output is shown below:

Fortune cookie binding.

check the copied message synchronously: Empty

Bon appetit.

crack now.

Copy message: A dream you have will come true.

check the copied message asynchronously: A dream you have will come true.

It shows that when checked in main(), the copy is still empty. In other words, it is impossible to use the copy in main(). Any functions that want to operate on the copy must be posted by the callback passed to Crack(). Posting and executing tasks asynchronously instead of invoking the function synchronously is essential in Chromium.

Interaction between Mojo Interfaces

To emphasize the asynchronous nature of Mojo interface calls, the last example looks at a more realistic use case. Two Mojo interfaces are defined, one is the client and one is the monitor:

interface RadiationListener {

OnRadiationLeak(string msg);

};

interface RadiationMonitor {

RegisterListener(RadiationListener listener);

};

This pattern is frequently used in Chromium, where the monitor class keeps an eye on certain external status (power, geolocation sensors etc.). When any events of interest occur, it notify the client class. The key for this to work is that early on during initialization, RegisterListener() must be called with a client passed in to be registered.

class RadiationMonitorImpl : public mojom::RadiationMonitor {

public:

RadiationMonitorImpl();

~RadiationMonitorImpl() override;

void BindRequest(mojom::RadiationMonitorRequest request);

void Drill();

void MeltDown();

private:

void RegisterListener(mojom::RadiationListenerPtr listener) override;

mojo::Binding<mojom::RadiationMonitor> binding_;

base::flat_map<int, mojom::RadiationListenerPtr> listeners_;

int next_listener_id_{0};

DISALLOW_COPY_AND_ASSIGN(RadiationMonitorImpl);

};

RadiationMonitorImpl defines two public methods Drill() and MeltDown, each send a different message to the client. The code is very similar to the implementation class seen before, except RadiationMonitorImpl uses a base::flat_map to store the registered clients and assign each an id.

On the client side, it prints different alarming string based on the message from the monitor:

void RadiationListenerImpl::OnRadiationLeak(const std::string& msg) {

std::cout << "listener received message:" << msg << std::endl;

if (msg == "drill") {

std::cout << "Don't panic.\n";

} else if (msg == "meltdown") {

std::cout << "Run for your life!\n";

} else {

std::cout << "err... not expecting this.\n";

}

}

Now let’s take a look on the main() function:

int main(int argc, char** argv) {

CHECK(base::CommandLine::Init(argc, argv));

base::AtExitManager exit_manager_;

// mojo requires a sequenced context, i.e., a message loop in the thread.

base::MessageLoop main_loop;

mojo::core::Init();

auto monitor = std::make_unique<prelude::RadiationMonitorImpl>();

auto listener = std::make_unique<prelude::RadiationListenerImpl>();

// create and bind the mojo interface pointer

prelude::mojom::RadiationMonitorPtr monitorPtr;

monitor->BindRequest(mojo::MakeRequest(&monitorPtr));

prelude::mojom::RadiationListenerPtr listenerPtr;

listener->BindRequest(mojo::MakeRequest(&listenerPtr));

// register the listener, note that this is async, note that move is needed

monitorPtr->RegisterListener(std::move(listenerPtr));

base::RunLoop loop;

// listener won't get this message as it's not registered yet

monitor->Drill();

base::SequencedTaskRunnerHandle::Get()->PostTask(

FROM_HERE, base::BindOnce(&prelude::RadiationMonitorImpl::MeltDown,

base::Unretained(monitor.get())));

base::SequencedTaskRunnerHandle::Get()->PostDelayedTask(

FROM_HERE, base::BindOnce(loop.QuitClosure()),

base::TimeDelta::FromSeconds(2));

loop.Run();

return 0;

}

The output is seen as below:

monitor bound.

listener bound

monitor drill.

register listener.

monitor detect meltdown

listener received message:meltdown

Run for your life!

As before, call to RegisterListener() through Mojo interface is asynchronous, which indicates the client is not hooked up when Drill() is called upon. So there’s no "Don't panic." printed in the output. On the other hand, MeltDown() is posted to the task runner and executed after RegisterListener(). Consequently, we see "Run for your life!" printed out as expected.

What’s missing in the big picture?

So far, we’ve covered the basics of Mojo interface. There are a couple of things still not quite right:

- In main(), the implementation instance must be explicitly created and bind to its Mojo interface request, which is tedious when there are multiple Mojo interfaces.

- More importantly, the code is tightly coupled, which is not a good thing considering that Mojo interface must work across the process boundary, that’s what IPC is all about.

This is where services comes to rescue.

Home